Early carved/incised and molded items

I

have bundled carved/incised and molded items together because the

application of the glaze (dipping) is similar. These are not strictly

speaking BoW items, however the timing of pure cobalt glaze use is

interesting. The earliest cobalt Iranian examples come from the 12-13th

century (

1,

2,

3, 4,

5,

6,

7, 8, 9) (I have also located one from Syria dated to the 11-12th century (

10)).

Decorative carving/incising predates this, however these items often

weren't covered in coloured glaze. Instead, an earthenware item would be

dipped in a white slip (clay) which would then be carved to reveal the

red/black of the original item before a clear lead based glaze was

applied over the top to seal the item (

11).

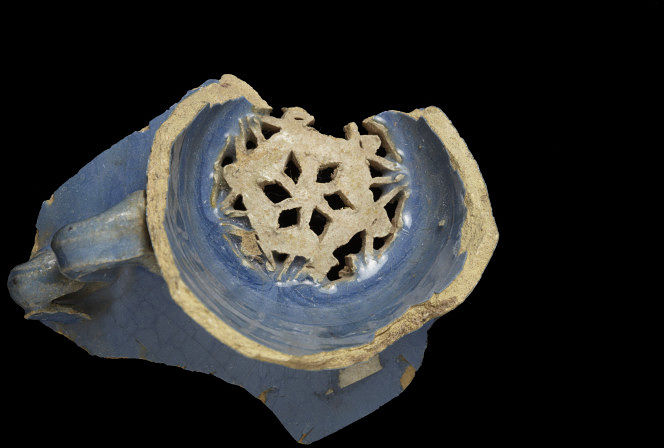

12th century

In the 12th century, Iranian potters seem to have started dipping carved items in a

thin layer of coloured glaze filling the deep cuts and outlining the

design (1-9). The dipping process (as opposed to submerging or painting)

is evident by the unglazed section of the foot, often featuring drips

of coloured glaze (

12). It is possible they adopted this method from Egyptian potters who were

using opaque green and turquoise glazes in this manner since the Ancient

Egyptian dynasties. Incised or moulded items were both produced in Fustat, Egypt (

13) as discussed in my

previous post on Egyptian BoW.

The Iranian potters also combined slip carving with coloured glazes. By applying a

black or white slip and then carving down to the coloured body of the

item, potters could then apply a single coloured glaze producing a dual-colour

item with only one firing required (

14). There seem to be many turquoise examples of incised items (

15,

16,

17,

18,

19)

but only a few cobalt. Perhaps this is because the cobalt is typically

darker and doesn't contrast well with the darker clay body. Colours such as brown (

20) and turquoise, seem to be utilised more frequently than cobalt for both molded (

21,

22) and incised (

23,

24,

25) items. Note the similar shape between the brown molded bottle (

20), and a Kashan striped bottle (

26).

In

addition to the dual-chrome incised items, potters had developed a style involving painting

multiple coloured glazes onto a carved item creating polychrome designs (

27,

28,

29).

I have yet to find an example of this in cobalt. I believe this is because cobalt works best on a white background, and the Iranian potters weren't using white opaque underglaze yet.

13th century

Later in the

13th century molded-ware seems to become the dominate form of dipped

cobalt items possibly due to ease of mass production. Items are molded out of stonepaste or earthenware (

30) before being glazed. This style seems to use a

thicker application of glazes so the raised sections, which are thinner and therefore lighter, outlined the design (

31,

32,

33,

34,

35, 36,

37, 38). At the same time, plain dipped cobalt ware was also being produced (

39,

40,

41, 42) across Iran.

Molded items could also be overglazed with lustre (

43) after the initial firing or have gold applied to the raised sections (

44,

45).

This is a relatively easy approach as the raised sections, especially

on flat items like tiles, are easy to gently grind away providing a

superior application surface for gilding. In addition, the sloped sides

of the raised sections provided a graded effect in the glaze and essentially highlight the

shape. Gilding is typically utilised for tiles as the gold is rubbed off with continued use so would not be appropriate for everyday vessels.

Interestingly,

a majority of the Iranian monochrome carved and molded items I found

were turquoise not cobalt blue. It could be argued that cobalt blue

ceramics

should occur frequently in Iran as the source of the

pigment is proximal making the glaze comparatively cheap (or at least

cheaper than their distant counterparts could source it). Though blue

did feature often, it was one colour in the glazier's pallet and

the predominance of turquoise suggests it was easier to mass produce or socially more desirable (perhaps the Egyptians love for turquoise plays a part here?).

Given this essay is focused on BoW ware, it behooves me

to mention the BoW radial striped items originating from Kashan (the

location of the cobalt resource).

Item 12 - Bowl, Iran, 12th - 13th century. Metropolitian Museum of Art accession no 12.72.3

Kashan BoW Striped Items

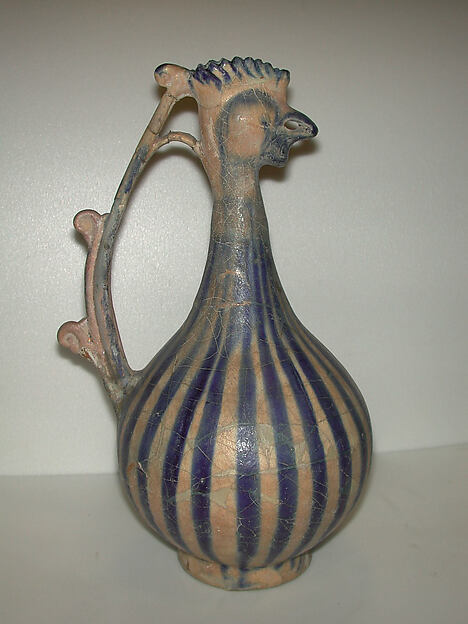

To date, I've collated a number of blue

and white radial striped items specifically listed as originating from Kashan.

Created in the 12th-13th century, this unique striped look was clearly

massed produced and applied to multiple forms. Bowls (

50,

51,

52,

53,

54), bottles/jugs (

26,

55,

56,

57), vases (

58,

59, 60), chicken headed ewers (

61,

62) and cups (

63,

64)

are all represented. This style cannot be examined in isolation (as

much as I like to make sweeping generalizations about BoW earthenware)

as there are a number of transitional items that show the BoW radial

stripes combined with other forms. For example, ewer

65 is molded, cast and pierced before being coated in tin-glaze and cobalt underglaze stripes (as is

66).

In this case, the striped design element has been utilised on a molded

piece rather than a built or thrown pots. This transitional piece

bridges the gap between the production of the radial striped works and

items such as this late 12th/early 13th century bowl

(67)

which has been completely covered in cobalt glaze. It suggests that

either, stylistically, the style evolved quickly or the

potters maintained several design 'lines'. Further evidence for this are

two transitional bowls (

68,

69)

which are identified as 13th century. Both bowls feature a combination

of the radial blue lines, with an inscribed black border and a central

roundel with fish. A third bowl (

70)

with radial cobalt lines sports a central black geometric decoration.

Produced alongside the radial BoW designs were blue and black floral

designs such as these bowls (

71,

72) and these cups (

73,

74,

75).

The cups feature a similar inscribed black band as the transitional

bowls as well as the floral and geometric design elements this Persian

style is known for. Additionally, the shape of both cups are extremely

similar to the BoW cups (13 & 14), particularly the unique design of

the handles.

Blue-black items dating from the 13th-16th centuries have been recovered from both Egypt (

76) and Syria (

77) suggesting this style was widespread. It's possible that this style was spread either by the movement of Iranian potters after the Mongolian conquests or later by the Mongols themselves throughout their empire.

Alongside the BoW ware and the Persian BBW items is a line of turquoise/black (

78) and lustreware (

79). This jug (

80)

is another bridging piece, with the turquoise/black glaze with radial

stripes and a black band of inscription.

Item 61 - Chicken headed ewer, Kashan, Iran. 13th century. The Metropolitian Museum of Art accession no 19.68.2

Kashan was also the

production center for tiles (such as those utilised in my

tile projects). Tiles produced in the 12th - early 13th century were typically lustreware (

81) but later evolved to a lustreware/cobalt or turquoise combination (

82) in the 13th century and later in the 14th century solid turquoise tiles (

83)

were featured. As cobalt and turquoise are both stable at high

temperatures, items can be underglazed, fired, then have a lustre

applied over the top (

84,

85).

In the 14th century plate decorations evolved too, with lustreware being used in combination with blue and turquoise glazes (

86), which in turn led to the evolution of Sultanabad-ware (

87), more of which can been seen in my

Sultanabad roundup or on my Saltanabad

pinterest collection. There is some suggestion that the methods of lustreware was brought to Iran via the migration of potters from Egypt who originally gained the information from the potters of Basra, Iraq.

I

have yet to find any BoW items labeled as being produced in Kashan

after the 13th century. (There does seem to be a recent revival of the

BoW striped pattern (

88)

which may be tapping into the antique market so care must be taken when

identifying Kashan BoW striped ceramics.) The mid-end of the 13th

century saw significant upheaval in Iran and Iraq

due to the Mongolian conquest. Thousands of civilians were slaughtered

or died of famine. This, undoubtedly, disrupted trade routes and

severely affected the arts.

It's possible that the workshops producing the blue and white radial patterns were shut down at this time or supplies of cobalt were limited as the focus of the labour force would have turned to recovery and food production. It's also possible that the demand for finely painted

polychrome or molded items led to the craftsmen turning away from the simpler radial designs and

BoW items. During this time, the Il-khanid period, Kashan was producing

lovely luster and cobalt/turquoise tiles well into the 14th century

which were utilised on many public monuments (

89).

Around the end of the 14th

century a majority of the tile production in Kashan had wrapped up.

This was due to the rise of the Timurid Dynasty which, at it's

peak, controlled Iran, Afghanistan, much of Central Asia as well as

parts of Pakistan, Syria and India. The capitol was based in Samarkland,

Uzbekistan, resulting in a political and financial focus significantly

further away from the Kashan potters. The Tamurid dynasty

experienced a greater Asian influence than previously seen in Iran. This was in part due to the location of their capitol and partly due to greater trade along the silk road routes. This influence is

reflected in the BoW items produced at the time.

Lustreware tiles from the 13th century. Tile Panel, Kashan, Iran. 1262. Victorian and Albert Museum, item numbers:

1837&A, C, E, F-1876, 1487-1876, 1489-1876, 1838&C, E-1876, 1077-1892, 1099&A-1892, 1100&A-1892