Blue on White ceramics: the reciprocal influence of Chinese porcelain on European and Middle Eastern ceramics - China

Other essays on the history of BoW in Iraq, Egypt, early Iran, late Iran, Japan, Turkey, Spain, The Netherlands, Italy and England.

China

Tang Dynasty (7th - 10th century)

Like many countries, some of the earliest examples of cobalt glaze in China are dipped earthenware items (1). This later developed into earthenware covered in white slip and painted with blue designs (2). These items were produced during the Tang Dynasty and may have been inspired by simple figurative bowls imported from Iraq. From the 9th century China started to develop "Porcelaneous ware" the precursor and bridge between earthenware and porcelain. Similar to earthenware, these items utilise a fine white clay, kaolin, which is an alumina-silicate (3). Fired at higher temperatures, the quartz (silica) fuzes creating the product often known as Mingware. Many glazes aren't stable at the higher temperatures required to create Mingware thus the decoration on the porcelaneous items remained simpler while earthenware items produced at the same time could be coated in a riot of colours like this yellow and blue phoenix headed jug (4) or this blue, green and brown box (5). These green, yellow/brown and blues items are often referred to as sancai-ware and would occasionally feature cobalt glaze (6, 7, 8, 9, 10). The sancai-ware became highly developed, with potters incising their designs to prevent the glazes from running together (11). Alongside the sancai-ware, the potters of the Tang Dynasty start to produced painted items such as this bird bowl (12) setting the stage for the development of the finely painted BoW items associated with China.

(As a side note, the Tang Dynasty also produced lovely earthenware of marbled clay, which I'm quite enamored of (13) )

Song Dynasty (10th - 13th century)

The Song Dynasty further developed the Sancai style producing complicated green and yellow motifs on incised earthenware such as Ganwa-ware from Mongolia (14) and Cizhou-ware from northern China (15, 16). These items however, do not seem to feature cobalt as the earlier style did. This was likely due to the difficulty of sourcing the cobalt for the glaze at the time.

In addition to lovely plain white porcelaneous objects, the Song Dynasty also produced distinctive items dipped in a light green / celadon glaze (17). Following the seemingly standard path of pottery development, the Chinese potters also experimented with under-glazing such as this light blue example with purple splashes dated to the 13th century (18).

Ming Dynasty (13th - 17th century)

It is generally accepted that the methods of creating porcelain had been well established by the 14th century in China. Porcelain had been endorsed by the Emperor who theoretically controlled all production and the export of porcelain items. The kilns of Jingdezhen produced all the imperial porcelain however there were private kilns creating imitations concurrently. For a good rundown with comparison images check out the Imperial Palace Museum's website here.

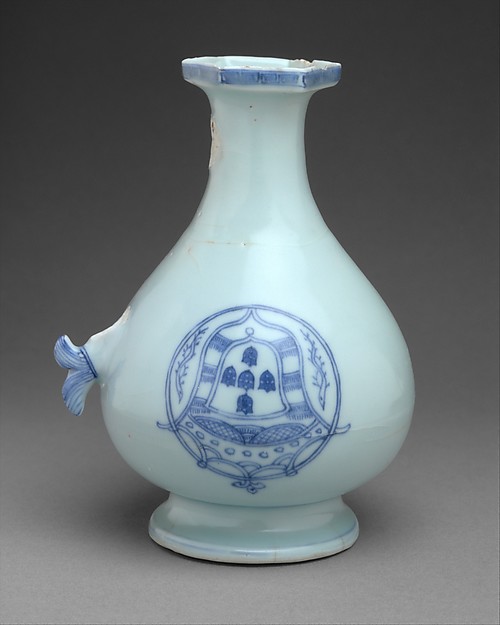

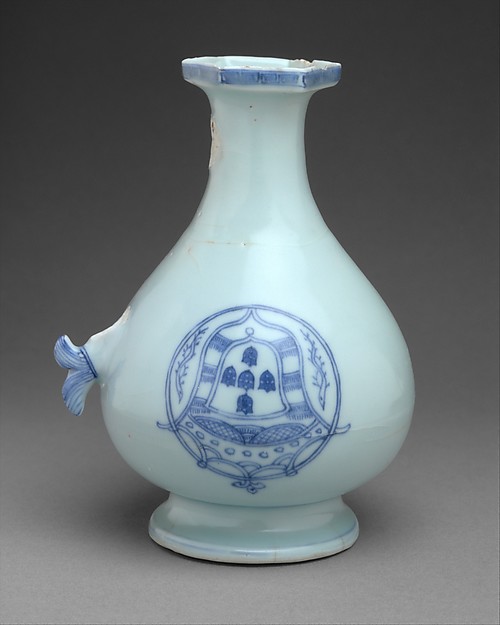

The kilns at Jingdezhen produced items both for export and domestic use. To appeal to the export market, the Chinese artists imitated design motifs from a variety of sources. A 1520's jug (20) is the earliest item identified as being deliberately created for export. It features the classic key design around it's rim seen on earlier porcelain items (21) as well as an upside down copy of the Portaguese arms. This plate from 1580-1600 featuring a Portuguese coat of arms for Captain Don Joao de Almeida (22) exemplifies the early attempts at leveraging the export market. The tiny coat of arms featured is framed by plumes and crested by a very awkward attempt at a helmet suggesting the artists had a weak grasp of the subject matter.

Item 21 - Ming-ware made for export featuring an upside down Portuguese coat of arms.

As trade along the silk road flourished and the European market increased, the export designs become significantly more refined and targeted. For example, this bottle made between 1662-1722 is very Persian with it's use of void space and stylised floral geometric patterns (24). The shape is also reminiscent of Iranian bottles popular at the time.. The imitation wasn't one sided, with the European and Middle Eastern ceramic centers creating their own imitations of Ming-ware. For example, these porcelain bowls created in 1600-1620 (25) spawned Iranian fritware copies (26). in the 16th-17th century, Chinese artists appear to have started adopting the Middle Eastern and European penchant for inscriptions in their work (27)

European countries weren't the only market or stylistic influence on the Chinese export trade. number of Ming-ware items also feature Mongolian style cloud designs which are a dominant feature in Turkey's Iznik design style (15th - 17th century) 28, 29, 30, 31. It seems that the Mongolian / Persian influence was quite extensive. This jar features archers wearing Persian style garments and is decorated with various vegetable motifs as well as images of European houses (32). This 17th century asymmetric dish shows the Chinese artists were also incorporating Japanese styles into their work (33).

Identifiable Chinese Design elements

The number 8 is considered lucky and linked to prosperity and wealth. This may be the reason why there is a distinct subset of Mingware incorporating 8 lobes of panels around the main decorative element (34, 35, 36, 37). The lobes very often feature auspicious symbols like a double gourd, a fan, a drum or a scroll. This subset of Chinese porcelain is occasionally referred to as Kraak after the carrak's of the Portguese traders who brought the goods to Europe. Porcelain is light and significantly stronger than the earthernware available that was available in Europe. This, in addition to it's link to the Chinese emperor, increased it's appeal as a status symbol. A number of renaissance paintings contain a blue and white porcelain bowl or ewer as a background feature. Rarer are those that celebrate the porcelain itself. The bowl featured in Treck Jan Jansz's (38) painting can be identified as Chinese in manufacture due to a combination of it's thinness, the sheen captured by the artist and the decorative lobes in the glazing.

The production and export of porcelain by the Chinese was the most significant factor in perpetuating the blue on white colour scheme as ceramic art became more sophisticated through the Renaissance and the range of colours available increased. Cultures which had well developed ceramic industries either renewed or built thriving local markets for the BoW goods. Chinese Kraak items were imitated by the Dutch (39), the Japanese (40), the Portuguese (41) and the Japanese (42). BY the 17th century, even the Spanish, who had several manufacturing hubs and a number of celebrated artistic trends were producing blue on white items for local consumption.

Like many countries, some of the earliest examples of cobalt glaze in China are dipped earthenware items (1). This later developed into earthenware covered in white slip and painted with blue designs (2). These items were produced during the Tang Dynasty and may have been inspired by simple figurative bowls imported from Iraq. From the 9th century China started to develop "Porcelaneous ware" the precursor and bridge between earthenware and porcelain. Similar to earthenware, these items utilise a fine white clay, kaolin, which is an alumina-silicate (3). Fired at higher temperatures, the quartz (silica) fuzes creating the product often known as Mingware. Many glazes aren't stable at the higher temperatures required to create Mingware thus the decoration on the porcelaneous items remained simpler while earthenware items produced at the same time could be coated in a riot of colours like this yellow and blue phoenix headed jug (4) or this blue, green and brown box (5). These green, yellow/brown and blues items are often referred to as sancai-ware and would occasionally feature cobalt glaze (6, 7, 8, 9, 10). The sancai-ware became highly developed, with potters incising their designs to prevent the glazes from running together (11). Alongside the sancai-ware, the potters of the Tang Dynasty start to produced painted items such as this bird bowl (12) setting the stage for the development of the finely painted BoW items associated with China.

(As a side note, the Tang Dynasty also produced lovely earthenware of marbled clay, which I'm quite enamored of (13) )

Item 11 - An incised sancai-ware tray. China, 8th century. The Met Museum item 1994.605.47

The Song Dynasty further developed the Sancai style producing complicated green and yellow motifs on incised earthenware such as Ganwa-ware from Mongolia (14) and Cizhou-ware from northern China (15, 16). These items however, do not seem to feature cobalt as the earlier style did. This was likely due to the difficulty of sourcing the cobalt for the glaze at the time.

In addition to lovely plain white porcelaneous objects, the Song Dynasty also produced distinctive items dipped in a light green / celadon glaze (17). Following the seemingly standard path of pottery development, the Chinese potters also experimented with under-glazing such as this light blue example with purple splashes dated to the 13th century (18).

Ming Dynasty (13th - 17th century)

It is generally accepted that the methods of creating porcelain had been well established by the 14th century in China. Porcelain had been endorsed by the Emperor who theoretically controlled all production and the export of porcelain items. The kilns of Jingdezhen produced all the imperial porcelain however there were private kilns creating imitations concurrently. For a good rundown with comparison images check out the Imperial Palace Museum's website here.

The kilns at Jingdezhen produced items both for export and domestic use. To appeal to the export market, the Chinese artists imitated design motifs from a variety of sources. A 1520's jug (20) is the earliest item identified as being deliberately created for export. It features the classic key design around it's rim seen on earlier porcelain items (21) as well as an upside down copy of the Portaguese arms. This plate from 1580-1600 featuring a Portuguese coat of arms for Captain Don Joao de Almeida (22) exemplifies the early attempts at leveraging the export market. The tiny coat of arms featured is framed by plumes and crested by a very awkward attempt at a helmet suggesting the artists had a weak grasp of the subject matter.

Item 21 - Ming-ware made for export featuring an upside down Portuguese coat of arms.

As trade along the silk road flourished and the European market increased, the export designs become significantly more refined and targeted. For example, this bottle made between 1662-1722 is very Persian with it's use of void space and stylised floral geometric patterns (24). The shape is also reminiscent of Iranian bottles popular at the time.. The imitation wasn't one sided, with the European and Middle Eastern ceramic centers creating their own imitations of Ming-ware. For example, these porcelain bowls created in 1600-1620 (25) spawned Iranian fritware copies (26). in the 16th-17th century, Chinese artists appear to have started adopting the Middle Eastern and European penchant for inscriptions in their work (27)

European countries weren't the only market or stylistic influence on the Chinese export trade. number of Ming-ware items also feature Mongolian style cloud designs which are a dominant feature in Turkey's Iznik design style (15th - 17th century) 28, 29, 30, 31. It seems that the Mongolian / Persian influence was quite extensive. This jar features archers wearing Persian style garments and is decorated with various vegetable motifs as well as images of European houses (32). This 17th century asymmetric dish shows the Chinese artists were also incorporating Japanese styles into their work (33).

Identifiable Chinese Design elements

The number 8 is considered lucky and linked to prosperity and wealth. This may be the reason why there is a distinct subset of Mingware incorporating 8 lobes of panels around the main decorative element (34, 35, 36, 37). The lobes very often feature auspicious symbols like a double gourd, a fan, a drum or a scroll. This subset of Chinese porcelain is occasionally referred to as Kraak after the carrak's of the Portguese traders who brought the goods to Europe. Porcelain is light and significantly stronger than the earthernware available that was available in Europe. This, in addition to it's link to the Chinese emperor, increased it's appeal as a status symbol. A number of renaissance paintings contain a blue and white porcelain bowl or ewer as a background feature. Rarer are those that celebrate the porcelain itself. The bowl featured in Treck Jan Jansz's (38) painting can be identified as Chinese in manufacture due to a combination of it's thinness, the sheen captured by the artist and the decorative lobes in the glazing.

The production and export of porcelain by the Chinese was the most significant factor in perpetuating the blue on white colour scheme as ceramic art became more sophisticated through the Renaissance and the range of colours available increased. Cultures which had well developed ceramic industries either renewed or built thriving local markets for the BoW goods. Chinese Kraak items were imitated by the Dutch (39), the Japanese (40), the Portuguese (41) and the Japanese (42). BY the 17th century, even the Spanish, who had several manufacturing hubs and a number of celebrated artistic trends were producing blue on white items for local consumption.

Item 38 - Detail, Still life with pewter flagon and two ming bowls. Treck Jan Jansz, 1651, National Gallery, NG4562

Additional references:

Valenstein, S.G, 1989. A handbook of Chinese ceramics. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Valenstein, S.G, 1989. A handbook of Chinese ceramics. Metropolitan Museum of Art.